In the mid-90s consultant and Harvard academic Clay Christensen published what went on to become a highly influential business text: The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. While Christensen’s explanation for corporate failure in the face of disruptive technology still resonates strongly, it is the case study he chose to illustrate it – the emergence of a mass-market for electric vehicles (EVs) – that makes for a fascinating read for car industry watchers in 2020.

Corporate Greatness to Corporate Failure

Clay Christensen was interested in why large, well-run and profitable businesses fail to adopt or fail to adapt to disruptive technologies. Think of the demise of Kodak (camera film), Blockbuster (video rental) and Xerox (the photocopier).

The conclusion from Christensen’s research was that while market champions are loaded with resources, they have hardened processes and a fixed set of values that rarely matches the new target market created by disruptive innovation. So, they are often very good (sometimes too good) at the sustaining type of change, but their corporate DNA prevents them from developing and/or adopting technology which would bring disruptive change to their core market.

At the end of his book, Christensen included a detailed case study on the commercialization and marketing of electric vehicles, focusing on the consumer car market. At the time that Christensen wrote the book, electric vehicles were still on what he called the ‘fringe of legitimacy’ due to technological constraints (primarily weight & range) but also their cost.

There was though, significant interest from car makers though, driven in the U.S by California Air Resources Board rules from the early 90s requiring that EVs account for at least 2% of their sales in the State. According to the book, in the face of California’s requirements, Chrysler planned to offer an electric version of their minivan for the 1998 model year at an estimated cost of $100,000, more than four times the sticker price for the gasoline-powered model!

The Rise of Tesla

Fast forward 25 years and although EVs still make up a modest part of auto sales there is no doubt that a mass market for zero- (tailpipe) emission passenger vehicles has been established. Growth has been rapid: global EV sales totaled about 1.1 million for the first half of 2019, an increase of 46% compared to the total sold in the first half of 2018 (EEI). COVID-19 appears to have done little to dampen consumers’ appetite for EVs and just last week Jarred Rystad, founder of Norwegian market analysis firm Rystad Energy, predicted that we would see one billion EVs on the road before the end of the 2030s.

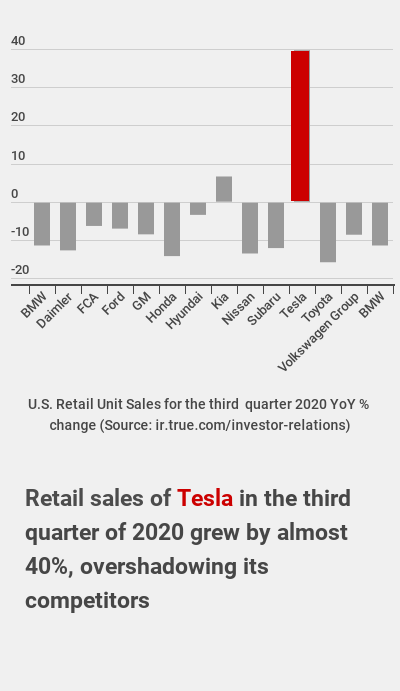

More than any other carmaker, perhaps more than all others combined, it is Elon Musk’s Tesla (TSLA) has been played the role of a technical iconoclast and market leader. The market turmoil of 2020 appears to have only strengthened its position. Consider:

- while like-for-like retail sales for the Q3 2020 were down across almost almost every other manufacturer, the company stood out with a 49.3% increase Y.O.Y. (Truecar forecast)

- sales of its Model 3 (already the top-selling EV globally) in the first half of 2020 outstripped its nearest rival by a factor of almost three to one (EV Volumes)

- Tesla has almost effortlessly overhauled General Motors as the largest US car manufacturer by market capitalization (and globally only trails behind Toyota), despite only having ~2% market share

So how true has the path blazed by Tesla been to that foreseen by Christensen 25 years ago?

What Christensen (correctly) predicted

The central theory of The Innovator’s Dilemma – that market entrants rather than existing market champions are best placed to succeed in commercializing disruptive technology – is certainly held up by Tesla’s rise in the EV market. Tesla, which was only formed in July 2003, is an archetypal disruptor. While Toyota, Nissan and Chevy did some pioneering work in the first decade of the 21st century, U.S. plugin EV sales show that the step change in sales that took place in 2017 was almost entirely due to the rapid expansion in Tesla sales (see U.S. Dept of Energy).

Christensen also rightly predicted that the carmaker that succeeds in creating a mass market for electric vehicles will be the one that resolves the battery ‘bottleneck.’ Tesla’s development of lithium-ion battery technology has been crucial to producing cars with a range acceptable to modern consumers but has also helped to position it as a clean energy company (in addition to a leading car maker.) When Tesla released the Roadster in 2008, its first production vehicle, it achieved 245 miles (394 km) on a single charge, a range unprecedented at the time for a production electric car.

Clay Christensen: “… without a major technological breakthrough in battery technology, there will never be a substantial market for electric vehicles.”

Batteries are so central to Tesla’s success that it holds ‘Battery Day’ events. At the most recent of these, in September 2020, the company announced that it plans to halve the cost of batteries.

A third – and equally notable – element to Tesla’s market strategy that was correctly foreseen in the Innovator’s Dilemma, was that the company that succeeded would create new distribution channels for electric vehicles. Christensen observed that “[r]etailers and distributors tend to have very clear formulas for making money… disruptive technologies…. often don’t fit [these] models.” Unlike other car manufacturers who sell their vehicles through franchised dealerships, Tesla uses direct sales.

Where Christensen came a little unplugged!

Not all of Christensen’s predictions about the rise of EVs proved to be correct for Tesla.

Firstly, Christensen predicted that the winning design in the first stages of the EV race would be characterized by simplicity and convenience and had to hit a low price point. On the contrary, Tesla took quite a different approach to getting its first vehicle into the market. Instead of trying to build a relatively affordable car that could capture the mass market, it focused instead on creating a compelling car, producing the Roadster. Retailing at around $100,000 this was well beyond the budget of most. Of course the Model 3 introduced in 2017 with a price that starts at $35,000 is a very much different proposition and transformed Tesla’s growth trajectory. Tesla is going even further; at its recent Battery Day event it promised a $25,000 car within three years.

Secondly, Tesla has also targeted a very different market segment from that envisaged by Christensen’s book. He anticipated that the breakthrough manufacturer would embrace the range limitations that were such an acute problem for EVs in the 1990s. “I would direct my marketers to focus on uncovering somewhere a group of buyers who have an undiscovered need for a vehicle that accelerates relatively slowly and can’t be driven farther than 100 miles,” That segment, he speculated, might be the parents of high school children looking for a safe vehicle and not concerned by limited range! Doesn’t sound very Tesla does it?! The Tesla founders were, instead, highly focused on the performance of their first car which could sprint from zero to 60mph in just 4.6 seconds and had a range of more than 200 miles.

Of course, the corporate history of Tesla has many chapters still to be written. The company itself recognizes the need for new, and potentially disruptive, technology. It will be interesting to watch how Tesla responds to the next wave of disruptive technology as the personal mobility market evolves.

Want to continue the conversation about innovation?