Having decided to pursue M&A (or even having found a potential target), a buyer needs to figure out how to finance the transaction. To the uninitiated, this can appear as a choice between using cash on hand and taking on debt. However, several other options are commonly used, and a shrewd buyer will consider them all.

In this article, we consider six of the most common sources used to finance acquisitions. We explore the pros and cons of each and some strategies about how/when to use the different funding options.

Common Sources of Deal Finance

- Cash Reserves:

The buyer elects to use its available cash reserves to finance the acquisition.

- Pros: No interest or additional debt burden; immediate transaction without external approval; no collateral or guarantee

- Cons: Reduces liquidity and reserves for other operations or investments

- Debt Financing (e.g., SBA Loans, Commercial Loans):

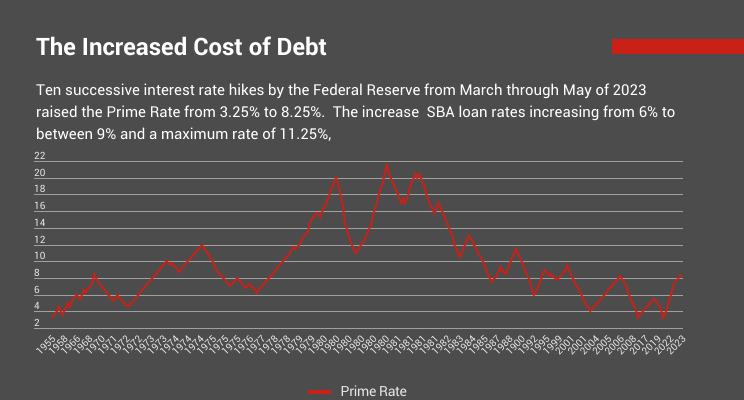

Debt financing sees the buyer borrow money to be repaid over time with interest. This can include loans from financial institutions, banks and lenders that provide Small Business Administration (SBA) loans and banks that provide larger commercial loans.

- Pros: Allows retention of full equity control; interest payments are tax-deductible; buyer can conserve cash reserves providing valuable liquidity

- Cons: Banks diligence/borrowing covenants; requires regular repayment regardless of business performance; can lead to high leverage; banks will require collateral and may also require personal guarantees; lenders rarely provide 100% of the acquisition price; the current borrowing environment is poor for many buyers (high-interest rates and a reduced borrowing options)

- Seller Financing (e.g., Seller Notes, Earnouts):

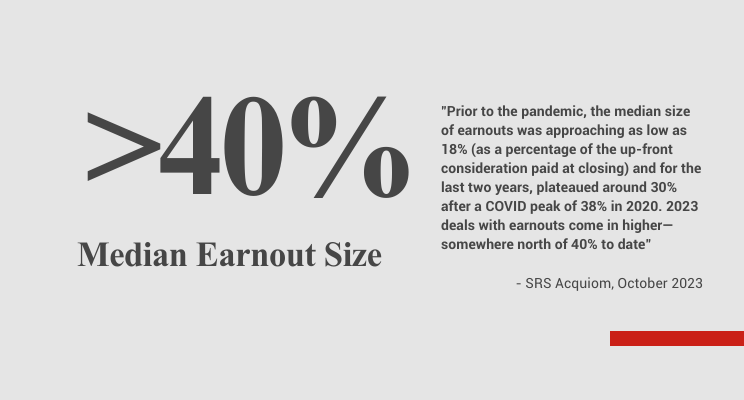

The seller accepts a deferred payment structure such as earnouts or seller notes, effectively extending credit to the buyer.

- Pros: Can facilitate deals with less immediate capital; aligns interests of buyer and seller and a good way to retain/engage sellers that remain working in the business)

- Cons: Seller retains risk; earnouts add complexity and can end in dispute

Seller finance in the form of both seller notes and earnout structures have increased in popularity over the last three years. Also, the average proportion of seller finance and earnouts used relative to the overall transaction has increased.

- Buyer Equity:

The buyer issues shares in its business in exchange for acquiring the target business.

- Pros: Preserves both cash and debt capacity; aligns seller’s interest with the target company’s future (and can retain/engage those working in the business)

- Cons: Dilutes current shareholders’ equity; unless the buyer’s shares are publicly traded, such an illiquid asset class may not be attractive to sellers

- Retained/Roll-Over Equity:

The seller retains a minority interest in the target or ‘rolls’ some of the proceeds from the sale back into a slide of equity in a newly created company that will own the target.

- Pros: Keeps the seller invested in the company’s success; reduces the cash needed upfront

- Cons: Buyer does not obtain 100% ownership; potential for conflicting interests if the seller retains significant influence; at some point, need to allow for an exit

- Third-Party Investment (e.g., Private Equity, Family Office):

The buyer raises equity capital from external investors like private equity firms or family offices.

- Pros: Brings in additional expertise and resources; can provide significant funding for acquisitions; higher risk tolerance that banks

- Cons: Involves sharing control; investors expect significant returns; at some point, will likely need to allow for the investor to exit

The right funding structure for your deal

No two deals are the same. In fact, two deals by the same buyer will often have different financing structures. This variety is driven partly by the buyer’s own position and partly by the outcome of what the buyer and seller negotiate.

A buyer, when considering its ideal finance structure, will take into account available cash reserves and its existing debt, the interest rate/borrowing environment and the buyer’s risk appetite. When it comes to negotiating the deal, additional factors shape things: the seller’s desire for cash up front, the seller’s risk appetite, whether or not the seller will remain working in the target business, the seller’s tax position and (of course!) the relative bargaining strength of the two parties.

At CNP we take a pragmatic approach to structuring deals, and encourage our clients to consider all available financing sources. Often, providing the other party with several different options to structure the deal can help reach a mutually acceptable structure quickly (and also demonstrates a willingness to address the seller’s priorities).

Where a buyer is considering third party financing, such as an SBA loan or private debt, it should approach lenders early in the deal process to get feedback on the potential deal structure. This will avoid any nasty surprises at closing.

Not necessarily a choice of either/or

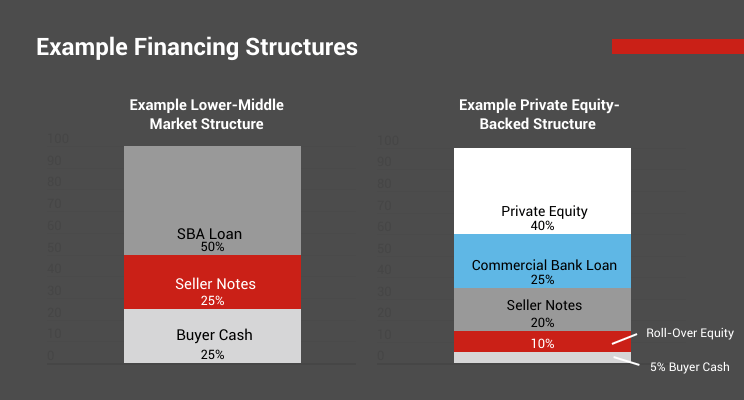

Most deals, at least in the middle market, employ multiple financing sources, rather than just one. For example, a typical lower-middle market transaction structure could see a buyer write an ‘equity check’ for 25% of the purchase price drawing on its own cash reserves, have the seller provide 25% of the price from in the form of seller notes and an SBA lender provide the balance (i.e. 50%).

Here’s an alternative, private equity-backed structure: 5% buyer cash; 10% roll-over equity for the founder/seller; 20% seller notes; 25% via a loan from a commercial lender and the balance (40%) from private equity.

Don’t forget about…

The buyer’s cost when acquiring a business aren’t confined to the purchase price. Both deal and integration costs can be material, and should not be overlooked. Lawyer, CPA, M&A advisor/investment banker fees quickly mount up. Once a letter of intent is signed, fees can quickly reach six figures.

An EY survey found that M&A transaction costs range from 1% to 4% of the deal value (see article here). Factors such as size and complexity of the target’s business, the availability/quality of information about the target business, the parties’ respective deal experience and risk appetite will push this up or down. Integration costs can vary significantly driven by the level of integration targeted by the buyer as well as the sector that the target operates in. EY found that for businesses acquired in health care and life sciences, the median M&A integration cost is 10.3% of the target’s revenue, driven by regulatory, safety and quality standards compliance, as well as consolidation in the health care research and development function. At the other end of the spectrum, the energy and utility sectors have shown relatively lower M&A integration costs, with a median of 3.9% of the target revenue.

Both deal and integration costs should be factored into the buyer’s financial model from the outset. A prudent buyer will also consider at the time of the deal how it will fund growth in working capital if it anticipates significant growth in the target business.

Got questions? We know M&A!

Do you have questions about deal structures or financing options? Unsure how you could fund a deal? Reach out to CNP today.